ADOBO

The name comes from the Spanish verb adobar, or ‘to marinate’, though it came to mean different things across the various culinary cultures subsumed into the Iberian empire – a dry marinade in the Carribbean, a wet one in Mexico, and so on. Spanish colonisers also applied the term adobo to the stewlike mix of spices and preserves eaten in the Philippines, because it seemed to resemble the blend of vinegar, salt, garlic and herbs often used back in the motherland. The additional key ingredient for Filipinos was the soya sauce introduced much earlier by Chinese traders.

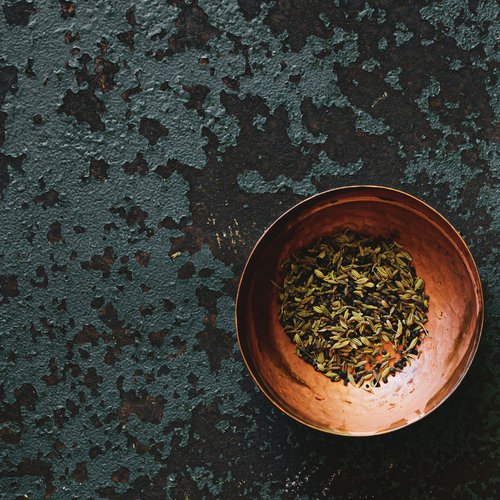

PANCH PHORAN

The term sphoton means ‘explosion’ in Sanskrit, and was gradually adopted and adapted to a tricky process of tempering whole spices in hot fat developed across the eastern states of India, and particularly in Bengal. Historian Pritha Sen has theorised that the origins of panch phoran lie in the Pala Dynasty of the 8th to 12th centuries, and its Buddhist fixation on the number five, as related to cosmology (five elements) and also to gastronomy (five key flavours). The five core spices of this mix (including cumin and fenugreek) are blended and tempered to subtly different recipes by families across the region today.

JERK SPICE

This hot seasoning has steadily become the signature flavour of Jamaica, used on all kinds of meat and fish, and bottled for sale in all manner of subtle brand variations. It was first developed by the runaway slaves known as Maroons, who escaped to the mountains and made use of what plants they found growing there – scallions, scotch bonnet chillies etc – to make marinades for the wild game they were able to catch. Two prevailing theories on the name suggest it comes from the jerking motion used to turn that meat over hot coals or to tear off chunks before serving.

PAELLA SPICE

Paella may well be the Spanish national dish, and Valencian farmers tend to get most of the credit for first cooking chicken and rabbit with rice in the flat pan from which the name derives. But spice-wise, its origins go back to the Moorish caliphates who first brought saffron to the Iberian peninsula, and perhaps even further to ancient Persian and Indian sources of the sweet paprika, fennel and turmeric that are still used to season the best paellas.

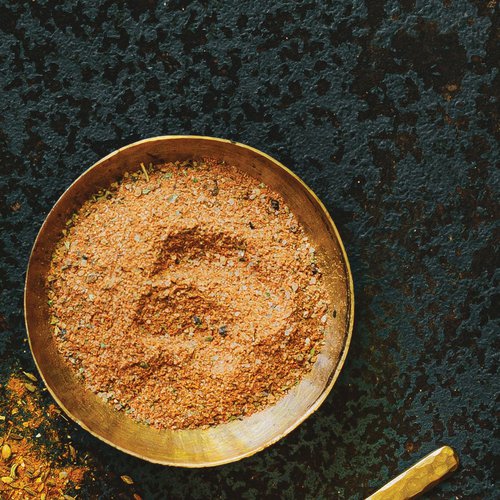

B'ZAR

Also known to some as Arabic Masala, or Emirati Spice Mix, this massively aromatic blend of pepper, cumin, coriander, turmeric etc is a core ingredient of cooking across the UAE. As eating in the region becomes ever more varied and cosmopolitan, there is a nostalgic familiarity to its flavour that is entirely specific to this stretch of the Gulf, especially as used in cholent, or chicken dishes. You might think of it as a universal compound condiment, which originally formed a kind of unifying spice bridge between the respective inland and coastal cuisines of the Bedouins and the fishermen.

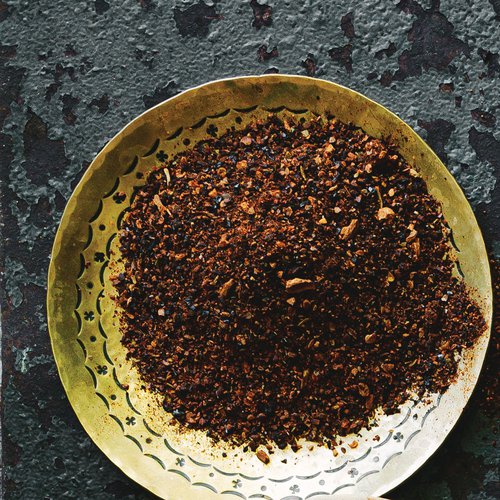

GUNPOWDER

Around the same time that the British military were using mixtures of actual gunpowder as toothache remedies and substitutes for salt and pepper at the ragged ends of their expanding empire, they also gave the nickname ‘gunpowder’ to the firecracker heat of the South Indian spice mix known locally as milagi podi. That term, in Tamil, simply means ‘chilli powder’, but the substance itself is a bit more complex, a kind of dry chutney seasoning that blends those ground peppers with lentils, sesame seeds, cumin and coriander, usually mixed with sesame oil or melted ghee to accompany idli or dosa.

BBQ SPICE

There’s a little anecdotal evidence that the idea of rubbing, or dusting, raw meat with a ground-up seasoning before cooking was first conceived in the colonial Carribbean, but there’s a lot more documentation for the art and/or science of barbecue preparation as a particular invention of the southern United States in the 19th century. Out on the ranges, a combination of necessity and abundance led farmers and frontier folk to grill their meat over open fires, and (perhaps inspired by Native Americans), they found that adding salt, sugar, hickory etc made for agreeable crusts or glazes while cooking at relatively low temperatures.

MIXED SPICE

The mix in question was originally derived from various ancient spices newly discovered and imported by the British from the furthest-flung reaches of their expanding empire in the 18th century. Cinnamon, coriander, nutmeg, ginger … all blended together into a sweet, mildly spicy compound that was first noted in the Mrs Frazer’s 1795 recipe book The Practice Of Cookery. Today the gingerbread aroma of mixed spice creates an instant, even tearful nostalgia among Brits, especially overseas, as it has long become associated with cakes, pies and puddings most commonly eaten at Christmas – for many it is the very smell and taste and essence of childhood

MOLE SPICE

Mole basically means “sauce” in the original Nahuatl language, and encompasses a whole family of wet concoctions across central Mexico. Some are relatively simple and quick to prep, others take days to make through a complex layering of dried chillies and other peppers with fruits and other seasonings. Many families in the Oaxaca and Puebla regions have inherited ancestral recipes passed down over centuries, most of which use a potent variety of chillies for flavour: guajillos, pasillas, anchos, and chipotles. Mole poblano, the most popular and widely exported variation, gains rich, deep colour and a bittersweet edge from the addition of cocoa.

DURBAN CURRY MASALA

Curry aficionados will affirm that the variants developed by the huge Indian population of Durban tend to be among the fieriest in the whole diaspora, using less cream and yoghurt while leaning harder on chillies, oil and spices. Key to the heat, sweetness and rich red colour of the Durban curry is the local masala mix. Its distinct flavour profile is derived from coriander, cumin and cinnamon – said to be the preferred spices of indentured labourers arriving in South Africa from the Chennai region over a century ago. Today that blend is essential to Durban’s signature street food dish, “bunny chow”.

HARISSA

During the Spanish occupation of Tunisia in the 16th century, locals developed a taste for the chillies latterly introduced to North Africa from the colonies of the New World. The story goes that shoppers at the souks would stand and wait for spice merchants to pound out a mix of those novel hot peppers with salt and olive oil – the name for that blend derived from the Arabic “harasa”, meaning “to break into pieces”. In the intervening centuries, its use has spread to the point that some estimates suggest that one full quarter of the world now eats harissa on a daily basis.

RAS EL HANOUT

Arabic speakers know the name of this rich and complex mix means ‘head of the shop’, a reference to its status as the very best product that spice merchants could offer in the Morocco of the Middle Ages. The legend says two camels got into a fight in the commercial hub of Sijilmasa, spilling their cargo on the ground and forcing the trader to claim that the resulting mess of spices was a fantastic new blend he had discovered somewhere between Cairo and Damascus. Besides creating intricate flavour, its 30-ish ingredients are said to have various health-giving properties, aiding digestion and acting as an antioxidant.