You’re behind the Middle East’s first farm to produce gourmet oysters. When and how did this start?

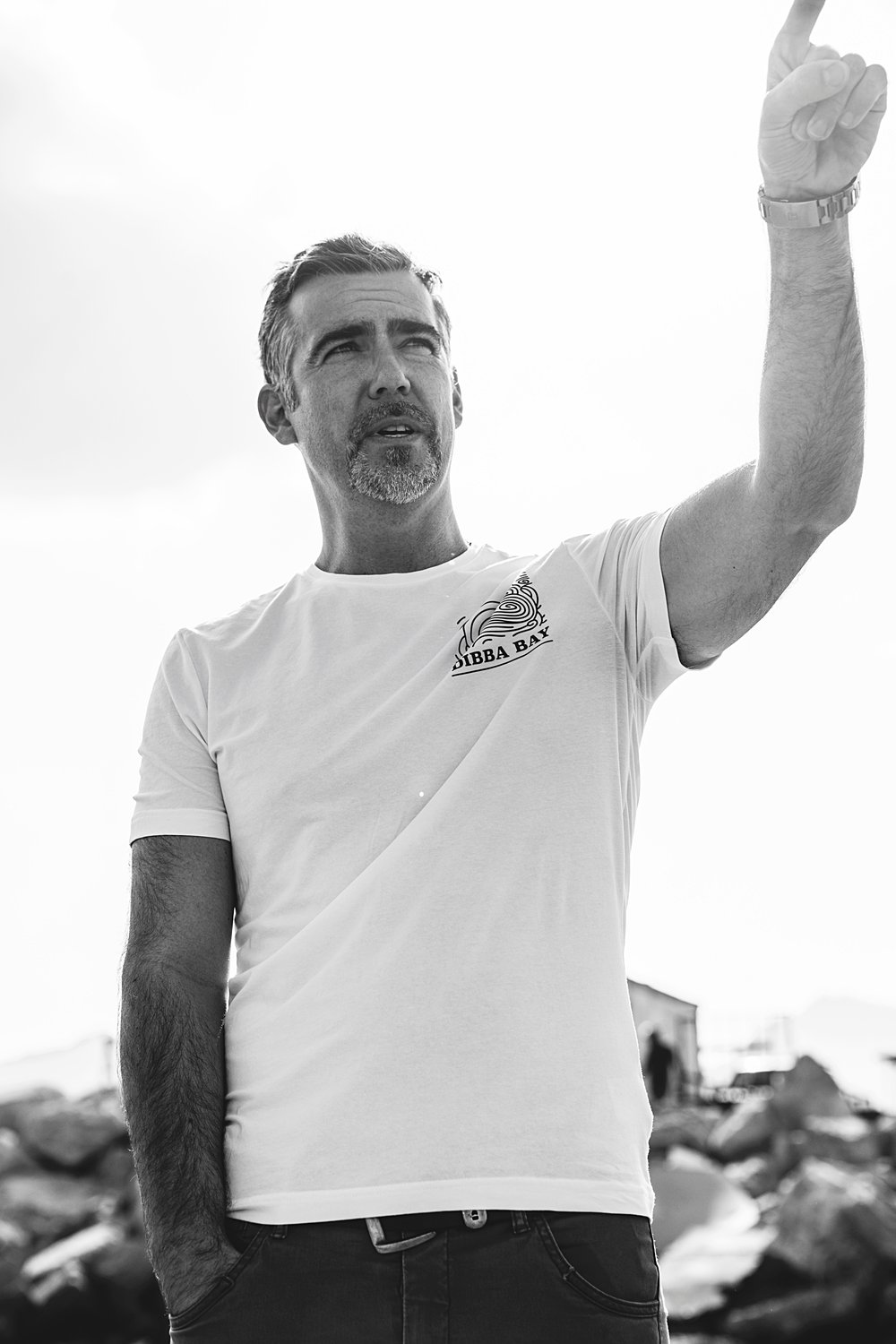

It began in 2016 as a speculative pilot study while I was trying to start a lobster farm in Oman. We were experimenting with aquaculture and tried to farm other species to test the environment. Among these was a batch of oysters. We placed them underwater, left them for six months, came back and found market-sized oysters waiting for us in the nets. I’m Scottish, but grew up in Dubai and I decided to move back to the UAE to set up the farm in Dibba because the government was supportive and open to projects of this nature.

What makes Dibba the perfect environment for oyster farming?

The surrounding sea water [the Gulf of Oman] is a good temperature, it’s pristine, home to so much plankton, and the salinity levels are lower than those of the Arabian Gulf. The area is not affected by any polluted rivers, industrial developments or large towns. And we’re the only oyster farm around.

Which species do you farm?

We’re cultivating the Pacific cupped oyster [which is native to the coast of Asia] that’s farmed everywhere from France to the US. This species probably accounts for 90 per cent of the world’s oyster harvests and this variety has done so well because of its adaptability to different climates. These oysters have a nice shape, are aesthetically pleasing and they taste great – they tick all the boxes.

Most of your operation takes place 500 metres offshore.

Yes, our main ocean concession is situated about 10km from Dibba Port and everything is set up four metres below the sea’s surface. We use a series of tensioned lines on which we hang mesh basket nets called ‘lanterns’. Each of these has different shelves, in which we place equal numbers of baby oysters (sourced from commercial hatcheries around the world). They’re spread out evenly, so that they’re all exposed to enough of the phytoplankton on which they feed. We start off with around 3,000-4,000 oysters per lantern and as they get bigger we reduce the number per level. When they’re fully grown, we will have just 200 oysters in each lantern.

How long do the oysters take to grow to market size?

This is the amazing thing about our oysters! In France, for example, it may take three to four years to get the oysters to grow to a good size like the big No. 2s (86-110g) we’re supplying to Spinneys. Ours take only nine months. This is largely because of the heat, and the massive amount of food that’s available to the oysters in the water. Generally, you’d only see growth rates peak like this in the height of summer in Europe – and it would only last for about two to three weeks.

How intensive is the farming process?

Anywhere else in the world you could leave oysters to grow on their own for six months at a time, but because ours grow so fast, we have to take constant care of them. We’re always looking out for predators such as barnacles, snails and crabs, and we have to haul them out of the water to clean, grade, weigh and sort the oysters on a monthly basis. It’s a hands-on process that sounds romantic, but is also intensive and time-consuming.

What happens once they’re fully grown?

No shellfish should be taken directly out of the ocean and served without being cleaned thoroughly. One oyster can filter roughly 170 litres of water over a 24-hour period, so we place them in settlement tanks filled with sea water that is sterilised by UV lights. It’s a three-day process that sees the oysters essentially cleaning themselves.

How does oyster farming impact the environment?

As filter feeders, oysters actually improve the local ecosystem and increase biodiversity. They clean the water, accelerate denitrification, enhance water clarity, and promote eel-grass survival. Interestingly, the lantern nets in which we keep the oysters get covered in weeds. They look like floating wreaths and act as nurseries where baby fish can feed and hide from predators and the summer sun.

How do farmed oysters differ to wild ones?

There’s no difference, really. Both types ultimately grow in the sea and are naturally organic.

And how do farmed oysters in Europe differ to your product?

The texture is different. Bigger oysters from Europe get their weight from fattiness, whereas ours are meaty and muscular. And there’s a good crunch when you bite into them. A lot of first-time oyster eaters appreciate this as they’re less ‘slimy’. The taste of our oysters varies according to the time of the year. In the summer they are less fatty, which means they are less sweet so the brininess comes through more strongly.

How do you like to eat oysters?

Because I eat them two or three times a week, I like variety. At the moment I’m experimenting with different ways of cooking them. But I’d always say that a squeeze of lemon works well with their salinity; they’re delicious with a red grape vinaigrette and finely chopped shallots, or with a drop of Tabasco for a bit of a kick.

Did you know?

Oysters are a good source of essential nutrients. These include vitamins A, E and C, vitamin B12, zinc, iron, calcium and magnesium. And you’ll find around 4-5g of protein in one Dibba Bay oyster.

Fresh protein category manager Steyn Liebenberg explains why sourcing locally is important.

“The UAE imports the majority of all food-related products, so exploring local alternatives will always be beneficial, not just from a freshness point of view but also to address other challenges such as food security," he says. "Spinneys is all about the fresher experience and Dibba Bay Oysters is a perfect example of this. We’re able to offer a locally sourced, gourmet-standard product that won’t break the bank.

Store and serve

Always keep Dibba Bay Oysters in the wooden box in which they’re supplied at Spinneys and place in the warmest part of your fridge. When ready to serve, shuck them, place them directly on a bed of ice and consume immediately.

How to shuck an oyster

Grab an oyster knife in one hand, wrap a tea towel over the other and follow these steps:

1 Hold the oyster firmly in the towel, with its flat-side up

and the hinge (where the shells meet) exposed.

2 Poke the knife into the hinge and twist it back and forth, using pressure, like you would to turn a key in a lock. Then gently twist

the knife to pop the top shell from the bottom.

3 Discard any excess water.

4 Slip the knife under the inside of the top shell to sever the adductor muscle. This will release the oyster and you’ll notice more liquid will appear. This is the good stuff that you want to keep in the shell as it’s packed with flavour.