From the earliest tribal campfires to the age of TikTok, barbecue has become America’s favourite food through a long history of adversity, diversity and sheer lip-smacking variety

The story of American barbecue is a long one. Records suggest that native tribes of what we now call the United States – as well as Central America and the West Indies – were digging pits to cook meat over fire for thousands of years by the time the Europeans arrived. The Taino people showed Christopher Columbus how it was done and the early white colonists of the Eastern Seaboard adopted that method through the 17th century. (The first written mention of “barbecue” comes from 1627.)

From there it proliferated across the southern states in particular. Cooking fires lit up the darkness all along the Mississippi River and around the Gulf of Mexico, hot coals glowing like stars on the endless open ranges of Texas. Today, it seems generally accepted that barbecue is the quintessential American cuisine, in the same way that jazz is the definitive American music. Adrian Miller would certainly concur, though he knows that some do not.

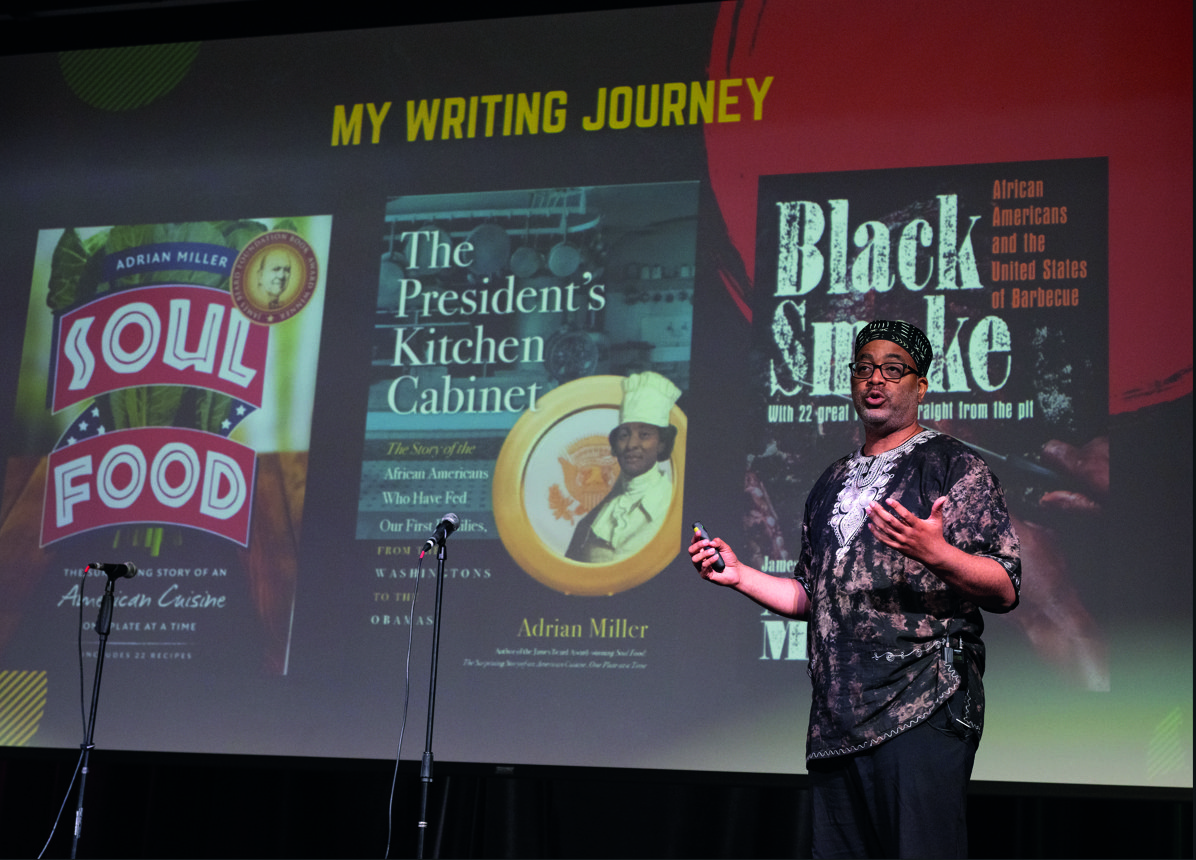

“These days you hear more people trying to argue that American barbecue is not exceptional, that it’s just part of a global grilling tradition,” says Miller. As a historian and author on the subject, a ‘soul food scholar’ per his Instagram handle, a consultant for Netflix’s Barbecue Showdown and a judge for the Kansas City Barbecue Society, not to mention a pitmaster in his own right, Miller is eminently qualified to insist that this practice “really is unique to our country”.

“If you look at the facts, no Europeans ever talked about barbecue, or cooked in quite this way, until they came to this continent. The word didn’t even exist.” As for his own African-American ancestors, Miller says he would love to believe that they had been the original inventors of barbecue back in their homelands of Ghana, Nigeria or Senegal.

“I wanted to prove that in my research, to be able to shout ‘Wakanda Forever!’ and drop the microphone. But nah, it wasn’t like that.” In his most recent book Black Smoke: African-Americans and the United States of Barbecue, Miller instead recounts how slaves displaced to Georgia, Alabama, Missouri and the like were introduced on the plantations to what was then a highly labour-intensive process, becoming experts “on a massive scale”.

“We’re talking 200 years ago when they had to butcher and cook the whole animal. This idea of grilling smaller cuts of meat is more of a 20th century thing that signals the transition from a rural context to an urban one.” After emancipation, African-Americans played an essential role in the spread of barbecue culture from the deep countryside to the big cities. “Those black people, now free, were getting on trains, boats and stagecoaches to come and make that Southern-style barbecue in other places where they put down roots. By the 1890s you start to see some of the earliest barbecue restaurants. Just shacks really, nothing fancy.”

Miller calls these pioneering chefs and owners “the first freelancers”. His book tells of figures like Henry Perry, who moved from West Tennessee to Kansas City in 1905. “Originally a hotel porter, he starts selling barbecue in alleys there and makes enough to open his own place in 1917. He’s been credited with teaching others how to cook and beginning that KC tradition.”

There are many such traditions across the barbecue belt, where different styles developed along the railway lines – depending on what types of farming the surrounding land supported and which animals were abundant as a result. “The thing about KC is that it was an agricultural crossroad, so all the different meats were coming through that way.”

In the cattle country of central Texas, meanwhile, the immigrant Europeans who came to open butcher shops found themselves with a daily excess of offcuts. “So they decided to smoke them and sell them to ranch hands and oil workers in that area and beef brisket dominated local barbecue. Then in Kentucky you’ve got a lamb and mutton tradition you don’t see in other places, and further down south you see a lot more chicken.” Fish has never had much of a place in American barbecue, says Miller, though a few pits are reserved for mullet in parts of Florida and for salmon in the Pacific Northwest.

Miller himself was born in Denver, Colorado, which is not especially renowned for barbecue, but his mother came from East Tennessee. She had her own method for cooking select meats, to be served with her preferred array of side dishes: coleslaw, potato salad, baked beans.

“Barbecue is often presented as dude food, but in the black community, women have a strong role and my mom was the grillmaster in our house.” In that same community, he explains, it is taken for granted that you know how to get that “good, strong charcoal flavour” from your chosen steaks, chops, or ribs, so it falls to the sauce or marinade to provide the personal signature of the chef. In his mother’s case, that particular sauce recipe was passed down from her father, who had worked the galley on the Southern Railroad in the 1940s.

Growing up to become something of an authority, and to hone his own skills on the grill (Black Smoke includes some of his own recipes), Miller has since sampled every regional style and variation, and he’s got his favourites for sure. He says, “Number one for me is probably KC, then Memphis is second, but Texas has been climbing the charts …”

At the same time, he admits, there’s a temptation to say that the “so-called Texas method” is not technically barbecue at all. “The way that this food developed in America was by digging a trench, filling it with wood and setting it on fire so that the coals got hot enough to cook the meat directly over them. What they’re doing in Texas is something different, because it’s indirect. They’re basically smoking the meat instead of grilling it. But I’m not about to roll down one of those places and say ‘Y’all aren’t barbecuing properly.’ All this stuff has been conflated now anyway.”

It’s arguably a curious time for barbecue culture. On one hand the cuisine itself is more popular than ever, as promoted by high-profile practitioners on social media and TV streaming networks.

On the other, says Miller, today’s celebrity pitmasters represent a narrow set of archetypes: “The bubba-type rural dudes, the hipsters with tattoos, the competition cooks with their syringes, the fine-dining chefs who now believe they have to show their chops by being good at barbecue.” Together, he says, they have led an “aesthetic shift” that now presents this method as more of a specialised craft and less of a working-class trade. A growing ignorace of the African-American contribution prompted him to write Black Smoke in the first place.

“Just as barbecue is becoming really popular, a lot of the big TV shows and magazines seem to have quite a limited focus. People love this food and they’re heavily invested, but if you’re new to it and you just want to know where to get the good stuff, you’re not really being given the full picture.” These days being the way they are, a lot of the aficionados like to police the boundaries of what is or isn’t “real” barbecue according to their own definitions.

“Some people just wanna fight,” says Miller. “The place it really happens now is in distinction between ‘low and slow’ and ‘hot and fast’. But there’s room for both, even if the faster-cooked meat will have a bit more chew. I think most would agree now that if it’s done in 15 minutes or less that’s just grilling, and anything else can be barbecue.”

At the same time, there’s surely a broader sense of community across this endless field of flames. The Kansas City Barbecue Society seems to be a case in point, with more than 15,000 members joining contests across the United States and beyond, submitting their house styles to the judgement of arbiters like Miller, while also respecting each others’ game.

He adds, “I absolutely think that we all share a strong belief that, as long as you eat meat, barbecue can bring people together. Even the fighting words are usually friendly and even more than other types of food, barbecue has this inherently social component.”

Consider all those grillmasters, all those ethnic backgrounds, all those family recipes, gathered around a single firepit and the quintessential American cuisine begins to seem like the very picture of the American Dream.