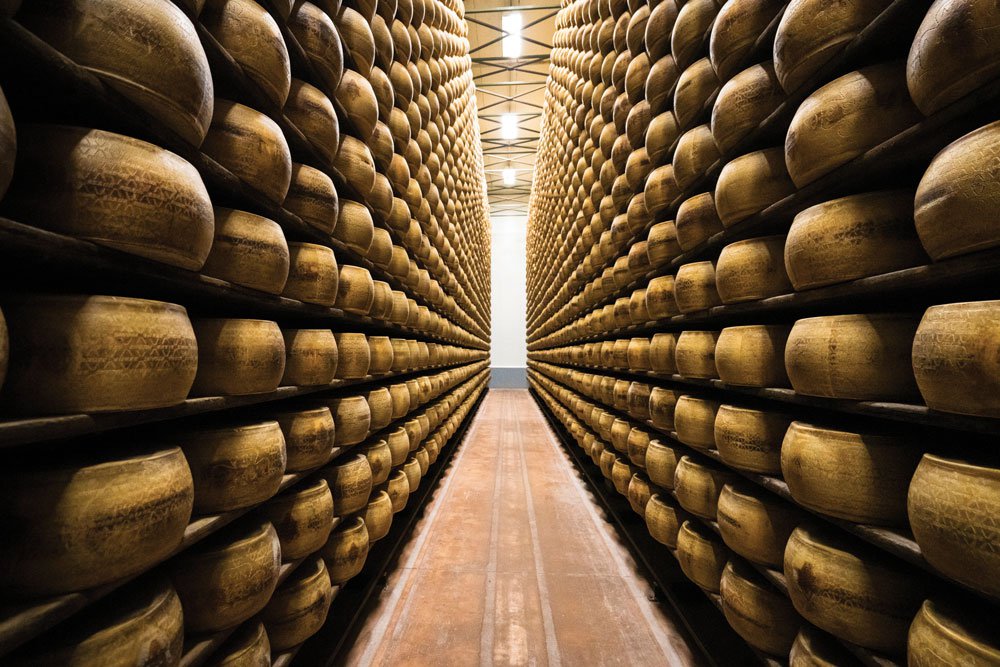

The maturation room looks (and smells) like a city built of cheese. Wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano are stacked into towers and arranged into honey-coloured rows that rise to form a kind of skyline beneath the vast warehouse roof. Thus surrounded by the product which is his life and his legacy, Paolo Zanetti knocks upon one of those wheels with a small hammer. He is listening for acoustical differences that might suggest holes or cracks in the structure.

“The sound is uniform,” he says. “That means no defects at all. This is basically a perfect cheese, ready to be packed for Spinneys.” Paolo wears a white lab coat over his shiny designer suit and a sanitary snood under the Zanetti-branded cap that covers his abundant curls. His bearing is that of a master artisan, successful businessman and eccentric scientist all at once. “When I was young I had months and years of this experience. I went to the dairy plant with my father and learned how to select the cheeses, checking wheel by wheel. It’s very important, before you sell, to understand what you’re selling, what the product really is.”

Fresian cows

Cutting into a wheel of Grana Padano

The Parmigiano Reggiano stored here at Zanetti’s Panocchia site, in the Parma province of Emilia-Romagna, is one of the two ‘kings of cheeses’ as Paolo puts it. The other, Grana Padano, is made at another Zanetti site, in its own specific production region on the opposite side of the River Po. There are many other cheeses in the range, but these particular items are especially renowned and coveted Italian delicacies, both officially certified under the auspices of Protected Designation of Origin (PDO).

“The best PDO products in the world,” says Paolo. “And I’m not just saying that because I am a Zanetti.” Indeed, he represents the fourth generation of a highly specialised cheesemaking operation that began with his great-grandfather Guido, circa 1900. After the second world war, his uncle Antonio set about industrialising the business, and Paolo himself was born in that transitional period when many Italian companies were moving out of the country’s city centres, though his childhood home still housed the main Zanetti factory in the basement. He was raised on the aroma, and played football with the workers as a boy.

“Quality...is our shared passion across every stage of the process, from the feeding of the cows to packing of the cheese, right until we deliver to Spinneys.”

The cheesemaker checks the consistency of the curd during the cooking process

Paolo Zanetti knocks a wheel of Parmigiano Reggiano with a small hammer to check for holes or cracks in the cheese

His grandfather Guido, meanwhile – son and namesake of the founder – started sending wheels to Switzerland, France and the US as early as the 1950s. Today, Zanetti is the top exporter of fine Italian cheeses, which are produced at multiple dairy plants and maturation facilities then shipped to 103 countries (including the UAE, where they’re sold under the auspices of the SpinneysFOOD brand).

Low-quality, generic replicas are also commonly sold in foreign markets as ‘parmesan’ or ‘granito’, or some other variation on the proper names and recipes. “They are copied because they’re fantastic products,” says Paolo.

He continues, “You don’t copy something if it’s not good.” If you’re looking for the real thing, you’ll find proof on the packaging and the rind itself, stamped with the official logos of the PDO designation and the regulating consortium.

The cheese-making process begins by boiling milk

Cheese is carefully placed in moulds

Obviously, the authentic product has an unfakeable flavour too, but some may struggle to tell the difference between these two superficially similar hard cheeses. Paolo is eminently qualified to outline the particularities of each, beginning with the separate production regions of Northern Italy in which each must be made to qualify for PDO status. Grana Padano is made with raw milk, he explains, while Parmigiano Reggiano mixes in 50 per cent partly skimmed milk (which is collected in the evening and separated from its cream overnight before blending with the full milk collected in the morning).

Precision is vital in terms of time and temperature – no more than two hours can pass in getting that milk from the cow to the vat, and the heat has to hit certain markers before and after the rennet is added and the curd is cut. And for all the new technology that Zanetti has invested in over the years, most of which is designed to help maintain consistency and certain modern sanitary standards, a large portion of this gastronomic art and science still resides in age-old, hands-on methodology, or what Paolo calls ‘manuality’.

A spinno is used to cut the curd

Excess milk being drained from Grana Padano

“Knowing the right moment to put the rennet in the cauldron, or to cut the curd with a spinno, then checking the consistency of the curd while it’s cooking … so much still depends on the experience and skill of the cheesemaker, who is really the key person inside the dairy plant.”

The finished mixture takes longer to mature than Grana Padano and the consortium will only fire-brand their approval onto the rind after a minimum of 12 months, though most wheels will be left to age for a further one to two years in the carefully controlled atmosphere of this enormous maturation house. The cheese that Paolo just hammer-tested began that process in September 2020, reaching an optimal 30 months old by the day of the Spinneys’ team visit. A matured Parmigiano Reggiano like this one has developed visible crystals across its interior, and a complex aroma with notes of butter, nuts, dried fruits, citrus and hazelnut.

Parmigiano Reggiano is manually cut into two halves

Salting room for Grana Padano

“I like to open a wheel myself,” says Paolo, “and to personally smell that triumph of flavours.” When it comes to actual usage, this particular cheese is ideal for grating over salads and pasta dishes, though he also recommends it as a table cheese or appetiser. Grana Padano has a softer, mellower, more delicate flavour. It’s also good for grating and melting, and goes especially well with sweet fruits like figs or dates, as well as platters like beef carpaccio.

“When you eat any of our cheeses, the taste is always great,” says Paolo’s second cousin Rodolfo, as he walks amid a herd of Fresian cows on the other side of the Po, in the Grana Padano territory of Lombardy. The cattle seem to know and love him, in his capacity as quality controller of the milk they supply, as well as of the finished cheese.

Grana Padano

The official Grana Padano stamp is only placed on a wheel once it has aged for a minimum of nine months

The youngest Zanetti in this family business, representing its fifth generation of cheesemakers, he too has been a part of the process since boyhood, surveying the dairy plants with his uncle (yet another Guido). What continues to amaze him about it, he says, is that the cheese tastes of “nothing” when the mixture is first boiled, but in only nine months – standard maturation for Grana Padano – “you get this fantastic flavour”.

Rodolfo, too, can easily rattle off the differences between this and Parmigiano Reggiano, not least the fact that the former is preserved with lysozyme, which is a natural enzyme found in everything from egg whites to human tears. But any Zanetti will tell you that the truly extraordinary thing about both cheeses is how little they have changed in the 1,000 years or so since they were first developed by local monks. Before Italy was Italy, those holy men found cheesemaking the best way to preserve the excess milk produced by the cows on the grounds of their monasteries. “These are both tremendously old cheeses,” says Paolo. “The technology has changed, but the ingredients are basically the same.” In that sense, the Zanettis see themselves as custodians, whose true responsibility is to maintain the quality of that ancient product.

“Quality is not just a word. It is our shared passion across every stage of the process, from the feeding of the cows to packing of the cheese, right until we deliver to Spinneys,” adds Paolo.